Written by Ray Hogan for Plutonic

Now that winter is behind us and the hoopla, hype and waiting lines of “Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back Again” (aka Warhol at the Whitney) seem just as distant a memory, the Museum of Modern Art has unveiled the true event of the New York art world of the first half of 2019 in “Joan Miro: Birth of the World.”

Drawing mainly from its own extensive collection, MOMA has put together a real dazzler, featuring 60 pieces ranging from 1917 to the 1950s. The Catalan born artist (1893-1983) doesn’t have the name recognition of other masters of his eras in part to his refusal to subscribe to any one particular school or style. But this sprawling exhibit should help correct that.

Fauvist? Cubist? Abstract Expressionist? Surrealist? Magical realist? He was likely all that and more if labels are necessary for description.

“I try to apply colors like words that shape poems, like notes that shape music,” Miro once said.

The show takes its title from “The Birth of the World,” an originally ridiculed 1925 masterwork and painting that wasn’t truly discovered until 1968. Set against a grey and blue background that curiously is without horizon. The painting depicts a black kite, a red balloon, and a rather amorphous figure holding on to the kite in effort to keep it from disappearing with the balloon.

Said Miro early in his career: “The moment I begin to work on a canvas, I fall in love with it, the love that is the daughter of gradual understanding. A slow appreciation of the manifold nuances, the concentrated glory of the sun. It is a joy to await an understanding of a blade of grass in the countryside — why belittle it? This blade of grass that is equally as beautiful as a tree or a mountain.”

The main lesson in “Birth of the World” may be that, even for a genre-hopping artist, that there was always representation in his abstractions. This is also the point where it’s probably best to explain that he split his time between Paris and Spain. He was viewed as a renegade, in some part, due to his contempt for conventional painting as a way of supporting high society and famously declared an “assassination” of painting, instead looking to upset the visual cliches of established painting and and styles. He studied both business and art in school until a nervous breakdown directed him in the direction of art alone.

Once the title piece finally snaps you back to reality, there’s more to see of this caliber. A lot more. In fact, several of the 60 pieces should not be missed.

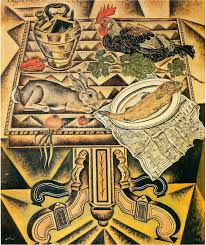

Let’s start with “The Table — Still Life with Rabbit” (1920). The table and space surrounding have been painted in stylized angular shapes, while the rabbit, fish and chicken atop the table appear to be alive, although clearly represented to be a food source.

Sticking with the still life theme are “Still Life — Glove and Newspaper” (1921), with its use of oranges, yellows and browns is startling alive. Jump ahead 16 years to “Still Life with Old Shoe.” Absolutely electric in its use of glowing color, this might be the piece that is most influential in today’s world, with elements of what would become graffiti, street art, rave and psychedelic styles and and various other forms apocalyptic and sensory enhanced vision.

No discussion of this monster of a show would be complete without a mentioning “Catalan Landscape (The Hunter)” (1923/24), perhaps the artist’s most identifiable work.

It also defined the symbolic language he would use for at least another 10 years. With floating parts set against an almost transparent background, real space and figure dissolves. Figures float seemingly at random (they’re not random at all) making this an absolute masterpiece. For more on his surrealist master see the carnival-like insanity see “Dutch Interior 1,” probably this writer’s favorite painting of the exhibit. Using a postcard of an old master Dutch painting, Miro transforms it into an almost theater of the absurd. A floating personage with a stringed instrument provides the focal point for an electric circus of household pets and a window view of the absurd. No doubt a songwriter like Bob Dylan had a paining like this in mind when penning some of his most lyrically opaque songs (“Desolation Row” and “Ballad of a Thin Man.”

“Joan Miro — Birth of the World” may be the rare big museum exhibit that merits a second visit.

See that MOMA has focussed on the first half of Joan Miro’s career, we can hope a latter-day retrospective arrives in a few years.

***

“Joan Miro — Birth of the World” runs at the Museum of Modern Art” (11 West 53 Street, New York, NY, (212) 708-9400 moma.org) through June 15.

Additional reading: “Miro” by Janis Mink” (Taschen)

Additional listening: Bobby Previte “The 23 Constellations of Joan Miro” (Tzadick)